First-past-the-post is a voting system that consistently and unpredictably skews election results in ways few can predict until the votes have been counted. The recent New Brunswick election results demonstrate this explicitly. But underneath the obvious deficiencies of first-past-the-post are some far more subtle and unsettling realities that are only possible under the first-past-the-post voting system.

1. The province-wide results were wildly disproportionate, but you knew that…

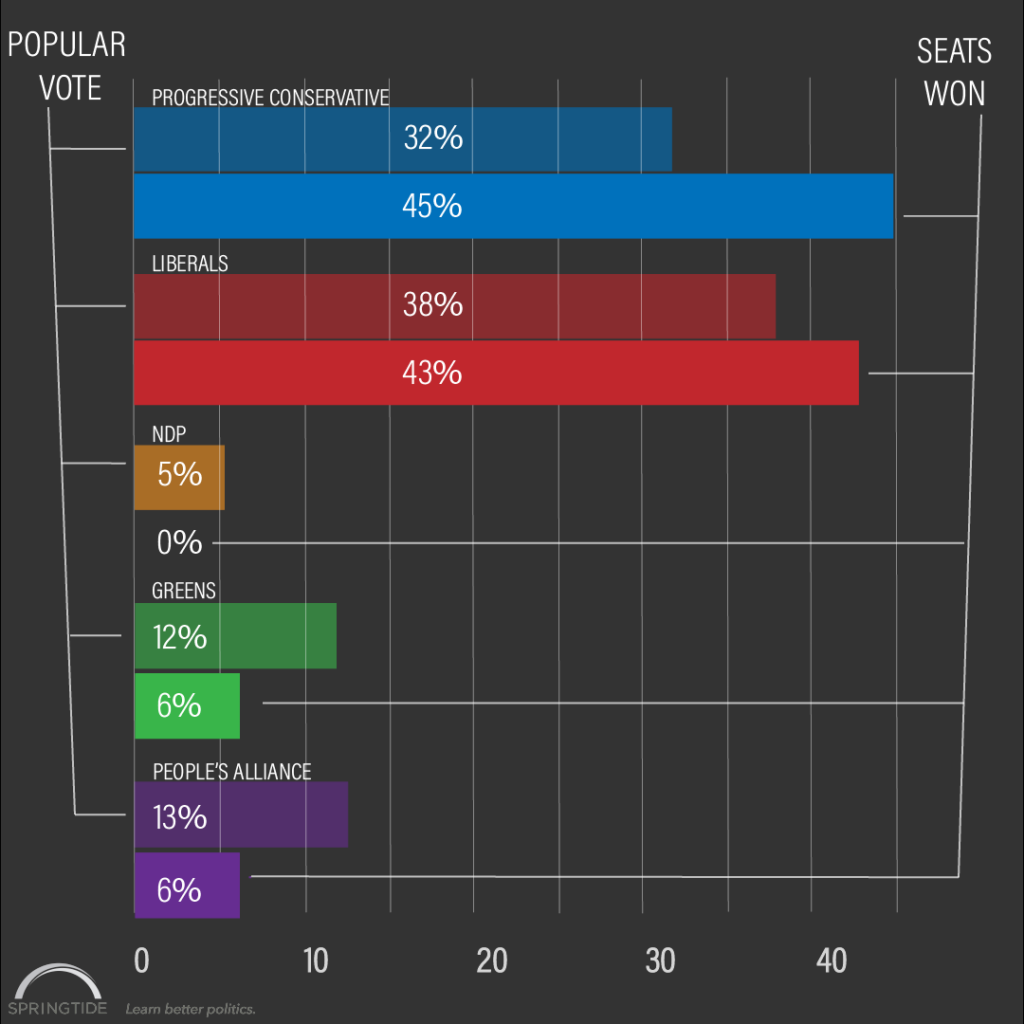

Despite the fact that Liberal voters outnumbered Progressive Conservative voters by 22,491 votes, the PCs walked away with 22 seats to the Liberal’s 21.

The Greens and People’s Alliance parties collected over 12% of the popular vote each, and both parties won three seats apiece in Monday’s election. For both parties, this represents a historic breakthrough, however, each party’s share of the popular vote (12 and 13%, respectively) is double their share of the seats in the legislature (6% each).

The failings of first-past-the-post, however, are about much more than the discrepancy between the share of the popular vote each party earned and the share of the seats in the legislature those parties receive. That’s just the beginning.

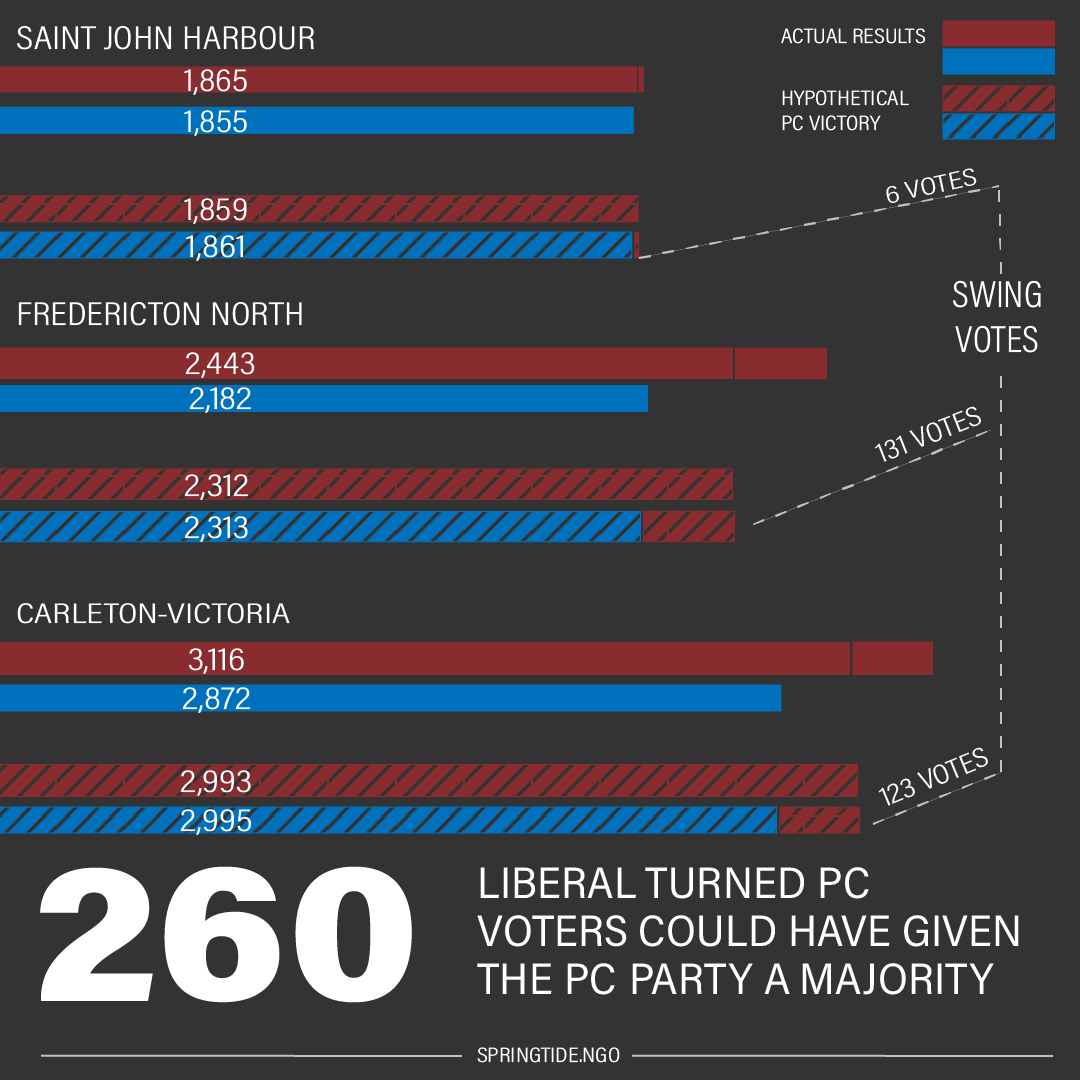

2. If 260 Liberal voters in three districts changed their minds, New Brunswick would have a PC majority

The Progressive Conservative Party, with 22 seats, ended up three seats short of a clear majority in the legislature. How many more votes would they have needed to work to earn a majority? Not many.

Consider the hypothetical scenario that would require the fewest number of voters to change their minds and vote for PC candidates. Take the three districts where PC candidates lost by the narrowest of margins – Saint John Harbour, Fredericton North, and Carleton-Victoria.

Take six Liberal voters from Saint John Harbour, 131 from Fredericton North, and 123 from Carleton-Victoria, and convince them to vote PC, and the party would have 25 seats, and a majority government. Had 260 voters chosen PC candidates instead of Liberals, all of the suspense and intrigue around last Monday’s election would be over with by now. The PCs would be the government, the Liberals would be reduced to a caucus of 18, and the Green Party and People’s Alliance caucuses wouldn’t be considered kingmakers.

Of course, these changes would have a minimal effect on popular vote. 260 ballots represents just 0.06% of the valid votes cast. New Brunswick would be governed by a PC majority government that had earned just 32% of the popular vote, 22,031 fewer votes than the Liberal Party. It didn’t happen, but it very easily could have.

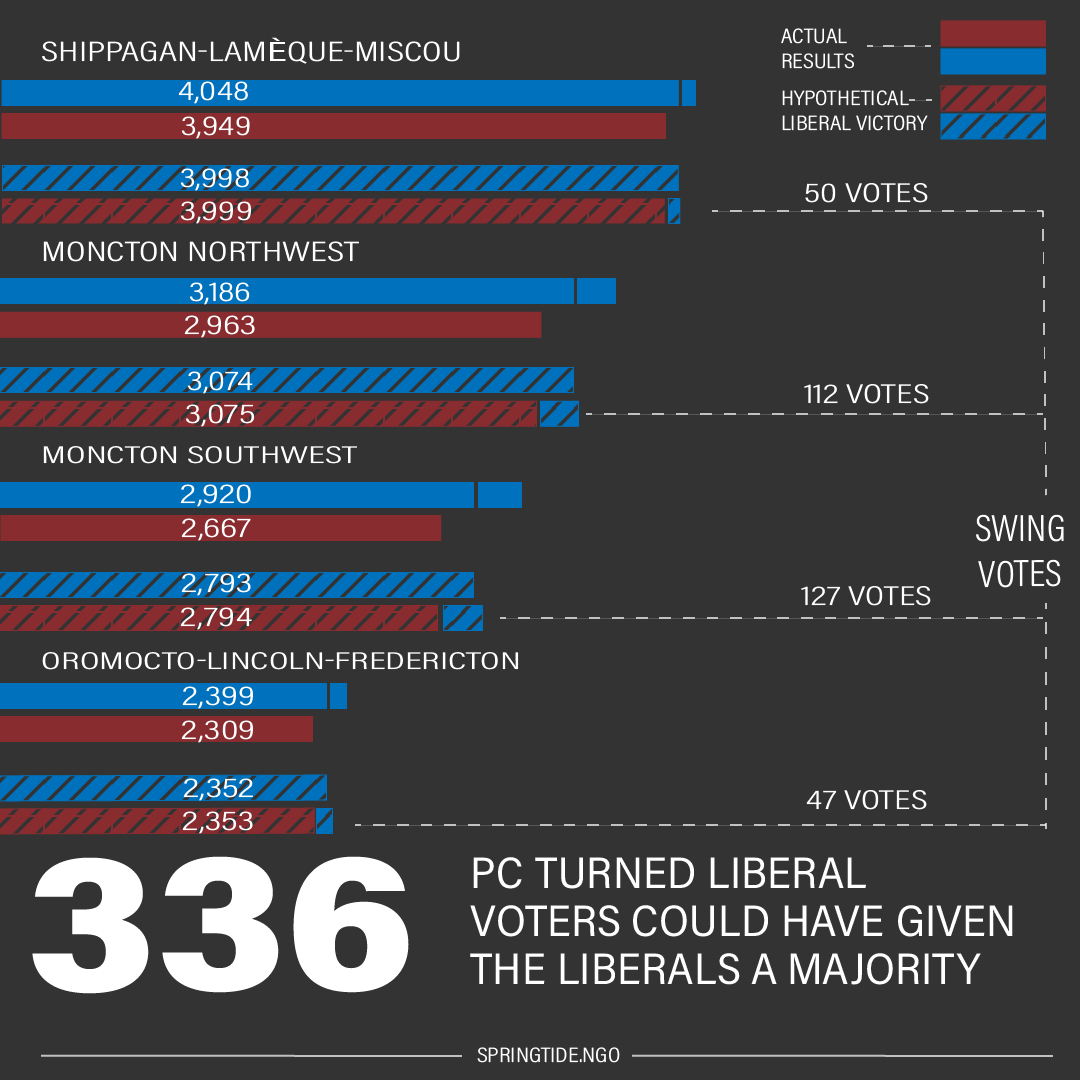

3. If 336 PC voters in four districts changed their minds, New Brunswick would have a Liberal majority

By the same logic, the Liberal Party wasn’t much further away from winning a majority government either. In a different hypothetical scenario, let’s imagine that 336 PC voters in Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou (50), Moncton Northwest (112), Moncton Southwest (127), and Oromocto-Lincoln-Fredericton (47) switched their votes to the second-placed Liberal candidates in those districts.

This would reduce the size of the PC caucus to 18, and give the Liberals the 25 seats needed to form a majority government. Again, such a subtle shift would barely impact the share of the popular vote registered for these parties (up 0.08% for the Liberals, down by the same amount for the PCs). The Green Party and People’s Alliance would have no role in determining which party formed the government.

Why these examples matter

Both of these ‘second-place switchers’ scenarios highlight the volatility of an electoral system like first-past-the-post. Subtle shifts in voting behavior within a small number of districts can dramatically change what form (majority/minority/coalition) and stripe(s) the government takes after an election.

Such volatility means that district-level polling is extremely valuable for party strategists. It incentivizes politicians to make parochial appeals on issues that only matter to voters in swing districts – even issues that only matter to swing voters in swing districts. More concerning, it makes elections far more vulnerable to the influence of bad actors with the means to conduct district-level polling.

But, for many partisan strategists, seeing numbers like these is the equivalent of seeing a four-out-of-five match on a slot machine. Any concerns about the legitimacy of the system and its results are too-often overshadowed by the desire to ‘pull the lever’ again, knowing how close victory actually was. A majority government isn’t tens of thousands of votes away, it’s just a few hundred.

4. Just 15 elected MLAs earned a majority of their constituents’ votes

In 34 districts candidates were elected without a majority of votes in their riding. Of the 15 candidates who earned a majority of votes, 11 are Liberals, two are PCs, one is a Green, and one is a People’s Alliance MLA. All four party leaders won their districts with a majority of support from their constituents. Trevor Holder (PC) was the only non-Liberal, non-party leader to win the majority of his constituents’ support.

5. 53% of voters have an MLA they did not vote for

Only 47% of voters cast ballots for someone that ultimately got elected.

6. Gerry Lowe’s victory shows how easy it is to get elected under first-past-the-post

Collecting 1,865 votes, Lowe had the fewest votes of all 49 elected candidates. But, that’s not what makes his victory worth mentioning. Gerry Lowe also won fewer votes than 32 of the losing candidates.

7. Wilfred Roussel’s loss shows how difficult it is to get elected under first-past-the-post

Wilfred Roussel lost the riding of Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou by 99 votes. He collected 3,949 votes of his own to Robert Gauvin’s 4,048. That’s more votes than any other losing candidate, twice as many votes as Gary Lowe, and more votes than 35 of the 49 elected candidates.

8. PCs lost support, but gained seats

The Liberals and the PCs both lost support compared to their own performance in the 2014 election. The Liberals dropped 15,057 votes, and won six fewer seats. The PCs earned 7,501 fewer and gained one seat. The Greens gained 20,604 votes, and grew their seat count from one to three, and the People’s Alliance gained 39,896 votes, giving them their first three seats.

| 2014 | 2018 | 2014 – 2018 | ||||

| Votes | Seats | Votes | Seats | Change in Votes |

Change in Seats

|

|

| Liberal | 158,848 | 27 | 143,791 | 21 | -15,057 | -6 |

| PC | 128,801 | 21 | 121,300 | 22 | -7,501 | 1 |

| Green | 24,582 | 1 | 45,186 | 3 | 20,604 | 2 |

| PA | 7,964 | 0 | 47,860 | 3 | 39,896 | 3 |

| NDP | 48,257 | 0 | 19,039 | 0 | -29,218 | 0 |

| Other | 3,293 | 0 | 3,187 | 0 | -106 | 0 |

| Turnout | 65% | 67% | ||||

9. We don’t have the democracy we think we do

The above examples are frustrating reminders that a democracy under first-past-the-post is a random and unfair form of democracy. All votes aren’t equal, not every vote counts, and the majority doesn’t rule.

—-

If you’re frustrated with first-past-the-post, consider supporting the Charter Challenge for Fair Voting, a court challenge aimed at fighting Canada’s discriminatory, first-past-the-post voting system.

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe. If you spot a typo, let us know.